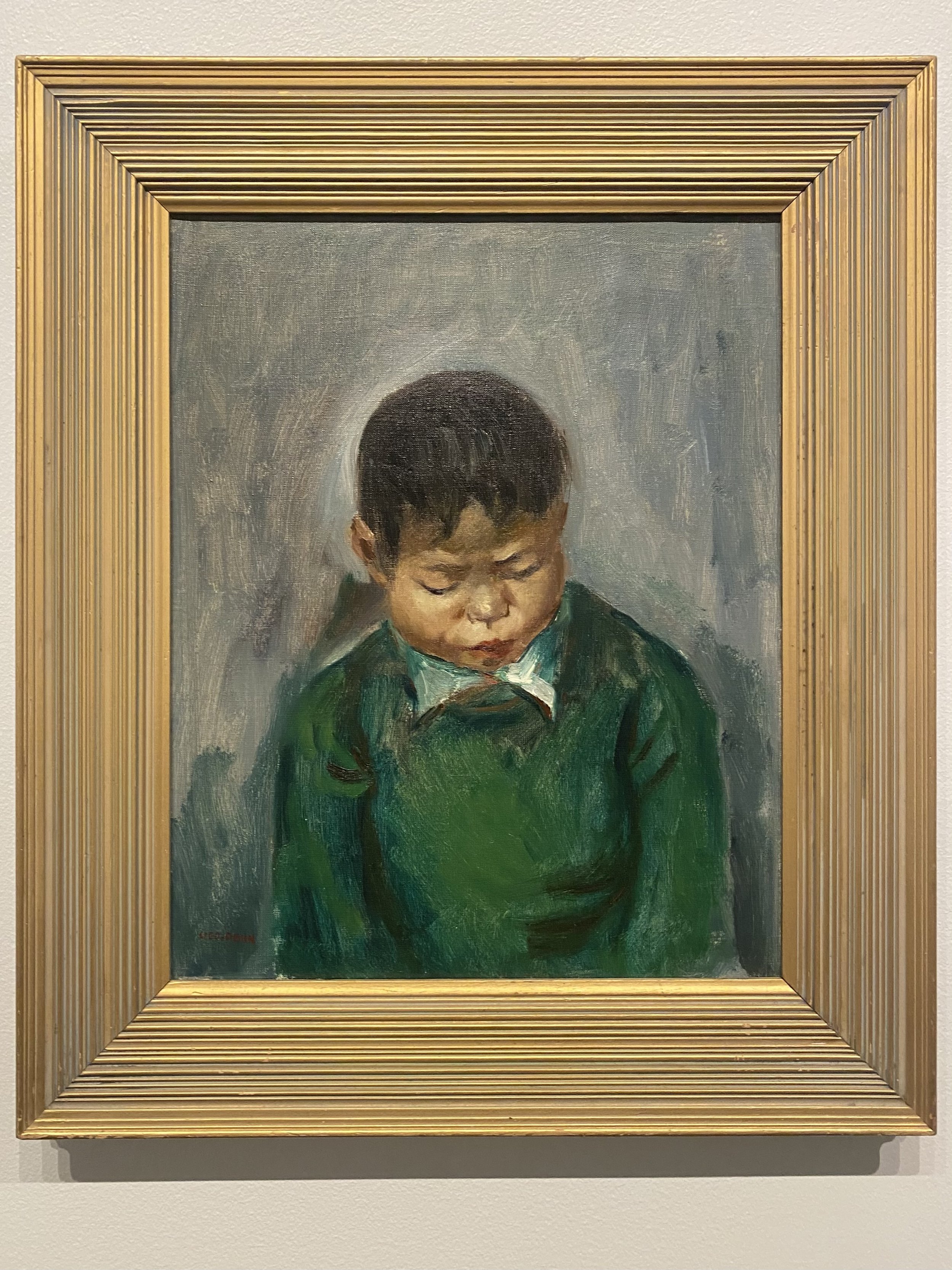

Green Sweater

Shy Boy, circa 1940, oil on Canvas by George Chann. Picture taken at Stanford University by the author.

The boy in the green sweater would not look up, his gaze fixed on the legs of the painter’s easel.

Who was this young painter making all these assumptions he would think back years later when recalling the occasion. He vaguely remembered some friend of the family, someone just as foreign as he was. When the painting was made, from those oil-based drips of green and grey and yellow and brown on the well-worn canvas, the only thing that occurred to this small boy was how much he preferred to be anywhere besides that uncomfortable stool in that cold, mundane studio.

“Come on, son, look up here. Nothing to be shy about.”

Nothing to be shy about, the child thought. What would this painter know of the humdrum sadness the boy felt on his day-to-day? Despite only seven years of age, he carried himself with the misbegotten angst and uncertainty of an old soul long since burdened with the pangs of isolation and misfittedness.

Just the day before, he had come to school, the only pupil there not like the rest. He grasped the lessons slower than the rest, he processed the directions given by his teacher with greater confusion than the rest, and rather than eliciting sympathy or patience from his classmates and his adult guardian, it seemed to only garner him ridicule and derision.

It was a negativity that pressed persistently into the duration of the school day, the emptiness following him as he walked across the playground, seeing all the other children playing on the monkey bars, riding on the slides, wishing he could join in their activities, knowing that he would soon be mocked by all for even suggesting such a ridiculous notion.

When the green sweater boy returned to his home, a humble apartment in a building forgotten by the city, where electricity was patchy and the air was damp, there in that small apartment he shared with his older brother, immigrant parents, and grandparents. There he would sit in his little corner and tend to the bruises on the interior of his mind, his confidence struck while it still attempted to build. He was coming of age when the inner workings of the child’s mind were still mostly an unmapped mystery, one that these parents and the rest of his community were ill-equipped to work with and understand.

His green sweater sat chokingly over the white-dyed, tightly-pressing, itchy uncomfortable fabric of his shirt. So when the painter asked him again: “Come on, son. Why don’t you look up?” He had hoped that the question would cease, for though he lacked the language to communicate everything that bothered him in this young life, he hoped that the wounded flutter in his eye would be enough to halt the painter’s interrogation.

Suffice it to say, his downtrodden disposition won the battle, and the painter ultimately went along with the weak posture, choosing to paint him as he wanted to remain.

Years later, the boy’s impression stood on the walls of a prestigious museum. In just the next room, paintings full of rococo jubilance and Dionysian sculpture were there to accompany him all day, and all night, while strange spectators looked upon the still-life nature of his downward expression. He never lived to see that this day, more people would relate to his frozen way, than the manufactured happiness that seemed always to surround him.